Principles of user-centred design

We share what we’ve learnt from running digital projects that are designed around the needs of their users.

All great digital products are designed around the needs of their users. Yet often organisations make assumptions about what users want, leading to projects designed to serve the needs of the organisation, not the needs of users. In our experience, such projects are far less likely to succeed than those that put the needs of users at the centre from the start.

User-centred design is one of those terms that sounds like common sense but can be tricky to implement in practice. So, we decided to distil what we’ve learned from creating user-centred digital products, offering you six key principles for delivering truly user-centred design.

Why is user-centred design important?

Before we dig into the ‘how’ of delivering user-centred design, we wanted to touch on why it’s important to centre users in all your digital projects.

User-centred design is designing for the needs of your users, rather than the needs of your organisation. This means it will often involve pushing back against parts of the organisation that believe they need certain solutions, without having spoken to users. You will have to constantly make the case for user-centred design, so it’s important to explain to stakeholders why it’s crucial to the success of your projects.

Sometimes managers think they have a better understanding of user needs than anyone, even the users themselves! The classic example is the apocryphal quote from Henry Ford that if he’d asked customers what they wanted, they would have said a faster horse. The irony in this example, so frequently employed by those pushing to ignore users and plough ahead with what they see as the best solution, is that Ford’s approach lost out to that of General Motors, who took user needs extremely seriously. From 1921 to 1927, Ford’s market share declined by 77%, whilst General Motors rose drastically. GM’s rise was driven by its consumer research-driven “a car for every purse and purpose” strategy that designed cars to serve users with different sets of needs.

The reality is that products developed to serve user needs are far more likely to be successful. In an attempt to quantify the value of user-centred design, McKinsey tracked the design practices of 300 publicly listed companies over a five-year period in multiple countries and industries. This research found a strong correlation between following user-centred design best practices and superior business performance, with those rated as being in the top quartile of design performance having 32% higher revenue growth than the average company in the study.

Be humble

Our first principle for effective user-centred design is the simplest and perhaps most important – be humble. You need to remember that for all your expertise, you are likely too close to the product. You are not the user, and you cannot let your insights overrule those of the people engaging with the product. You must keep an open mind, rather than going into the project with a set of assumptions you are looking to prove.

This mindset will help you approach the project in the right way. For example, you may find that the problem you’ve set out to solve isn’t the right problem. You’ll need to stay humble to let go of the solution you had in mind and pivot to solving the problem users have identified as being the most crucial. Being open and humble is key to keeping any user-centred project on the right track.

Use the double diamond approach

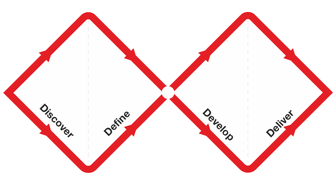

To give structure to your user-centred design projects, we recommend using the “double diamond”. This is a method of product development from the design council that lays out the best way to approach the various stages of the user-centred design process. Put simply, it is a four-step process, where the first “diamond” is how you decide on what the right thing to make is, and the second diamond is how you make that thing in the right way.

In the ‘discover’ phase at the start of the project, you should be expansive, seeking to understand the full spectrum of users' problems, and not closing off fruitful areas of inquiry just because they don’t conform to your initial assumptions. Then, in the ‘define’ stage, you need to decide on a tightly defined issue you will tackle, so you don’t try to solve all of your problems at once, leading to a messy, ineffective solution.

That’s the first half of the diamond complete. In the second half, during the ‘develop’ stage, you take an expansive approach again. This is where you think about how you’ll create a product to solve the tightly defined user problem you established in the define phase. Explore the problem from different angles and brainstorm a wide range of possible solutions. This lets you think creatively without restrictions. Then finally in the ‘deliver’ stage, you need to pick a single idea so you can focus on the most promising and effective solution.

Use problem statements to get specific

As you follow the first half of the double diamond approach, you’ll initially identify lots of issues users face, then narrow down on the most important for you to solve. A useful principle is to get very specific at this stage. We recommend you do this by writing a tight problem statement.

Writing a problem statement lets you condense a lot of information into a couple of sentences, which helps guide the future direction of the project and keeps it focused. It also acts as a checklist to ensure you’ve correctly defined your audience, your problem and how you’ll measure the impact of your solution. Here’s the template we use to write effective problem statements:

We believe that [audience] has [problem] and that [solution] may solve this problem by [this aspect] and [that aspect].

We will know when this has succeeded when [quantitative measure] and [qualitative measure] reaches [this target].

Writing this out lets you think about the problem methodically. We find this structure leads to clearer thinking and ultimately better outcomes.

Map out your users’ journeys

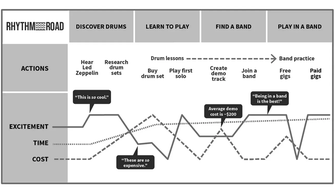

To be user-centred, your design should meet the needs of your users at all times, not just during the touchpoint you’re focusing on. To see things from the point of view of your users, we recommend creating an ‘experience map’ to plot out the journeys users take and understand what they need at different points along that process. An experience map should capture not only what the user is doing (such as signing up for an event) but also what they are thinking and feeling. This allows you to tailor not just what you say at each stage, but also how you say it.

In the example below, you can see an extremely simple version of an experience map, tracking how prospective drummers are likely to feel over their journey to becoming musicians.

Image source: IxDF

The journeys your users take will be very different to the simple example above, but by mapping them out you’ll identify where potential pain points are. You will also be able to think in a more structured way, tailoring your messaging or product to the needs of the user. For example, if you know users rely on a certain service you offer at a stressful time, then you’ll want to make sure you speak to them in a reassuring tone at that stage. You should also think about how you can reconfigure what you’re asking users to do at this stage to remove any pain points that might exacerbate this stress.

Don’t conflate user research and user testing

User research and user testing both are crucial to user-centred design, but they each have a distinct role to play. It’s important to understand this principle so you can use the right technique at the right time.

The separate roles that they play map neatly to the double diamond introduced earlier in this post. User research addresses the first diamond – ‘making the right thing’, and user testing addresses the second diamond ‘making the thing right’.

User research is for understanding who your users are, what they want to achieve, and the barriers that get in the way of achieving it. Use it to explore the issues they face when they use your digital services to inform your solutions. See our articles on starting user research and running user interviews for more information on how to conduct effective user research.

User research identifies problems, but don’t make the mistake of asking users to come up with solutions. Users are not design experts, so asking them how to solve problems won’t be useful. You need user experience and design expertise to take the problems you identify and successfully architect solutions that solve them.

Once you’ve designed the solutions then it’s time for user testing. This is where you test if the solution you have proposed actually solves the user's problems. It’s best to involve users very early in the design process, to allow you to identify any incorrect assumptions straight away and correct them before you spend a long time developing your solution. We recommend setting up user panels for your key audiences. You can then draw upon these to quickly get real users testing prototypes, so you don’t have to recruit from scratch every time you want to conduct user testing.

To get feedback early, you should take an agile approach and develop a minimum viable product ‘MVP’ early on. Use this to run an ‘alpha’ version of the product, getting early feedback from a small pool of invited users, and then a public ‘Beta’ to get more data on how users respond to what you’ve created. For more information on how to work in an agile way, we recommend the agile delivery service manual from gov.uk.

Adopt a mentality of continuous improvement

True user-centred design is a lot like painting the Forth Bridge- it’s never done. User needs are always evolving, and you’ll need to evolve with them. That’s why our final principle is to adopt a mentality of continuous improvement.

The best feedback you’ll ever get is from real users. When you come to launch your product, don’t see it as the end of the project. The launch is the biggest user testing session you’ll ever have. Taking this attitude helps change your organisation’s mentality towards receiving feedback. A customer telling you that a form on your website is clunky could be taken negatively, but when you’ve adopted a mentality of continuous improvement, you’ll see that interaction as a big positive – you’ve increased your level of insight and now understand more about how you can improve that process to increase that form’s conversion rate. You should always be inviting and collating feedback so that when the time comes to revisit the project, you’re ready with plenty of user insight.

Putting it into practice

We hope you will find these principles useful as you apply them to your user-centred digital projects. If you want expert help to understand your users, then take a look at our user insight service. When the time comes to put this insight into practice, our digital brand and user experience service can deliver user-centred designs for your digital estate.